在古代苏美尔人,巴比伦人,亚述人,埃及人,希腊人,罗马人,印第安人和中国人的著作中,可以追溯到创造全身麻醉状态的尝试。在中世纪,大致相当于有时被称为伊斯兰黄金时代,科学家和其他学者在穆斯林世界和东方世界的科学和医学方面取得了重大进展。

文艺复兴在解剖学和外科技术方面取得了重大进展。然而,尽管取得了这些进展,手术仍然是最后的手段。很大程度上是因为相关的疼痛,许多外科疾病患者选择了某种死亡而不是接受手术。虽然关于谁应该对发现全身麻醉最值得赞扬的问题存在很多争论,但人们普遍认为,18世纪末和19世纪初的某些科学发现对现代麻醉药的最终引入和发展至关重要技术。

19世纪后期发生了两项重大进展,它们共同促成了向现代手术的过渡。对疾病细菌理论的理解迅速导致了防腐技术在外科手术中的发展和应用。防腐很快让位于无菌状态,将手术的总体发病率和死亡率降低到比以前更为可接受的速度。与这些发展同时发生的是药理学和生理学的重大进展,这导致了全身麻醉的发展和疼痛的控制。

在20世纪,通过气管插管和其他先进的气道管理技术的常规使用改善了全身麻醉的安全性和有效性。监测和具有改善的药代动力学和药效学特征的新麻醉剂的显著进步也促成了这种趋势。在此期间出现了针对麻醉师和护士麻醉师的标准化培训计划。 20世纪末和21世纪初,经济和工商管理原则在医疗保健方面的应用越来越多,因此引入了转移定价等管理实践,以提高麻醉师的效率。[1]

1846年10月16日,William T. G. Morton在波士顿马萨诸塞州综合医院的Ether Dome重新制定了第一次全身麻醉演示。 外科医生John Collins Warren和Henry Jacob Bigelow被Southworth&Hawes列入这个daguerrotype。

Bulfinch大楼是Ether Dome的所在地

目录

1“麻醉”的词源

2 古代

2.1 鸦片

2.2 古典时代

2.3 中国

3 中世纪和文艺复兴

4 18世纪

5 19世纪

5.1 东半球

5.2 西半球

6 20世纪

7 21世纪

8 参考

“麻醉”的词源

“麻醉”一词,由奥利弗·温德尔·霍尔姆斯(Oliver Wendell Holmes,1809-1894)于1846年从希腊语ἀν-创造,“没有”; 和αἴσθησις,aisthēsis,“sensation”,[2]指的是对感觉的抑制。

古代

全身麻醉的第一次尝试可能是在史前时期进行的草药治疗。 酒精是已知最古老的镇静剂; 数千年前,它被用于古代美索不达米亚。[3]

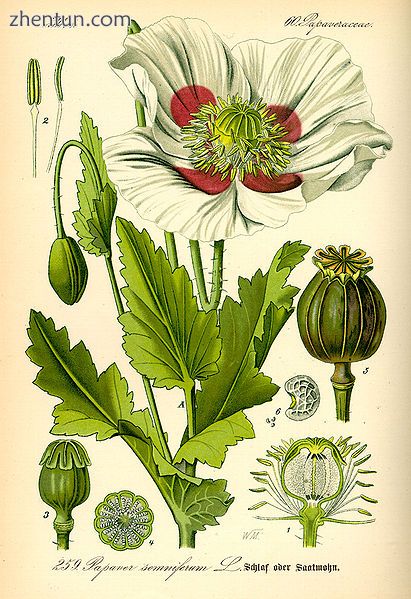

鸦片

罂粟,罂粟花

据说苏美尔人早在公元前3400年就已经在下美索不达米亚种植和收获了罂粟(Papaver somniferum)[4] [5],尽管这有争议。[6]迄今为止发现的关于罂粟的最古老的证词是在公元前三千年末用小白泥板刻在楔形文字上。这款平板于1954年在尼普尔发掘期间被发现,目前保存在宾夕法尼亚大学考古与人类学博物馆。由Samuel Noah Kramer和Martin Leve解读,它被认为是现存最古老的药典。[7] [8]这个时代的一些苏美尔人的片剂上刻有一个表意文字,“hul gil”,翻译成“喜悦的植物”,一些作者认为是指鸦片。[9] [10]在世界某些地区,吉尔一词仍用于鸦片。[11]苏美尔女神尼达巴经常被描绘成罂粟花从肩膀上长出来。大约公元前2225年,苏美尔领土成为巴比伦帝国的一部分。因此,罂粟及其欣快效应的知识和使用传递给了巴比伦人,他们将帝国向东扩展到波斯,向西扩展到埃及,从而将其范围扩展到这些文明。[11]英国考古学家和楔形文字学家Reginald Campbell Thompson写道,鸦片在公元前7世纪为亚述人所知。[12] “Arat Pa Pa”这个词出现在亚述草药中,这是一种日期为c的刻印亚述片的集合。公元前650年。根据汤普森的说法,这个术语是亚述人对罂粟汁的名称,它可能是拉丁语“罂粟”的词源。[9]

古埃及人有一些手术器械,[13] [14]以及粗制镇痛药和镇静剂,包括可能是从曼德拉克水果中提取的提取物。[15]手术中使用与鸦片相似的制剂记录在Ebers Papyrus中,这是一种写于第十八王朝的埃及医学纸莎草。[11] [13] [16]然而,古埃及是否知道鸦片本身是否值得怀疑。[17]希腊神Hypnos(睡眠),Nyx(夜晚)和Thanatos(死亡)经常被描绘成持有罂粟花。[18]

在将鸦片引入古印度和中国之前,这些文明率先使用了大麻香和乌头。 C。公元前400年,Sushruta Samhita(来自印度次大陆关于阿育吠陀医学和外科手术的文本)主张使用含有大麻香的葡萄酒进行麻醉。[19]到公元8世纪,阿拉伯商人将鸦片带到了印度[20]和中国。[21]

古典古代

在古典古典中,麻醉剂被描述为:

Dioscorides(De Materia Medica)

盖伦

希波克拉底

Theophrastus(Historia Plantarum)

中国

华佗,中国外科医生,公元200年

Bian Que(中文:扁鹊,Wade-Giles:Pien Ch'iao,公元前300年)是一位传奇的中国内科医生和外科医生,据报道他使用全身麻醉进行外科手术。它被记录在韩非大师书(约公元前250年),大历史记录(公元前100年),以及比安赐给两个人的李大师书(公元300年)中。 “Lu”和“Chao”,一种使他们失去意识三天的有毒饮料,在此期间他对他们进行了胃造口术。[22] [23] [24]

华托(中文:华佗,公元145-220)是公元2世纪的中国外科医生。根据“三国志”(公元270年)和“后汉书”(公元430年),华坨在全身麻醉下使用他将葡萄酒与草药提取物混合而制成的配方进行手术。叫做mafeisan(麻沸散)。[25]据报道,华坨使用mafeisan甚至进行了切除坏疽肠等重大手术。[25] [26] [27]在手术前,他给了口服麻醉剂,可能溶解在葡萄酒中,以诱导无意识状态和部分神经肌肉阻滞。[25]

mafeisan的确切构成,与华陀的所有临床知识相似,在他去世之前就烧掉了他的手稿。[28] “三国志”或“后汉书”中没有提到麻醉粉的成分。由于儒家教会认为身体是神圣的,手术被认为是一种肢体残割形式,因此在中国古代强烈劝阻手术。因此,尽管华坨报道了全麻的成功,但中国古代手术的实践以他的死亡告终。[25]

mafeisan这个名字结合了ma(麻,意为“大麻,麻木或麻刺”),fei(沸,意为“沸腾或冒泡”)和san(散,意思是“分解或分散”,或“药物”粉末形式“)。因此,mafeisan这个词可能意味着“大麻煮沸粉”。许多中医学家和中医学者已经猜到了华坨mafeisan粉末的成分,但确切的成分仍然不清楚。他的公式被认为包含了以下几种组合:[25] [28] [29] [30]

bai zhi (Chinese:白芷,Angelica dahurica),

cao wu (Chinese:草烏, Aconitum kusnezoffii, Aconitum kusnezoffii, Kusnezoff's monkshood, or wolfsbane root),

chuān xiōng (Chinese:川芎,Ligusticum wallichii, or Szechuan lovage),

dong quai (Chinese:当归, Angelica sinensis, or "female ginseng"),

wu tou (烏頭, Aconitum carmichaelii, rhizome of Aconitum, or "Chinese monkshood"),

yang jin hua (洋金花, Flos Daturae metelis, or Datura stramonium, jimson weed, devil's trumpet, thorn apple, locoweed, moonflower),

ya pu lu (押不芦,Mandragora officinarum)

杜鹃花,和

茉莉根。

其他人认为该药水可能还含有大麻,[26] bhang,[27] shang-luh,[22]或鸦片。[31] Victor H. Mair写道,mafei“似乎是与”吗啡“相关的一些印欧词汇的转录。”[32]一些作者认为华佗可能已经通过针灸发现了手术镇痛,并且mafeisan要么没有做或只是他的麻醉策略的辅助。[33]许多医生试图根据历史记录重新制作相同的配方,但没有一个达到与华佗相同的临床疗效。无论如何,华佗的公式似乎对主要业务没有效果。[32] [34]

从古代用于麻醉目的的其他物质包括杜松和古柯的提取物。[35] [36] [37]

中世纪和文艺复兴时期

阿拉伯和波斯医生可能是最早使用口服和吸入麻醉剂的医生之一。 Ferdowsi(940-1020)是一位住在阿拔斯王朝的哈里发诗人的波斯诗人。在他的国家史诗“Shahnameh”中,Ferdowsi描述了在Rudaba进行的剖腹产手术。由琐罗亚斯德教牧师准备的特殊葡萄酒被用作此手术的麻醉剂。[22]虽然Shahnameh是虚构的,但是这篇文章仍然支持这样的观点,即至少在古代波斯中已经描述了全身麻醉,即使没有成功实施。

1000年,Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi(936-1013),一位被称为手术之父的阿拉伯医生。[38]住在Al-Andalus,发表了30卷的Kitab al-Tasrif,这是第一部关于手术的插图工作。在这本书中,他写了关于全身麻醉用于手术的文章。 C。 1020年,IbnSīnā(980-1037)描述了在医学佳能中使用吸入麻醉。佳能描述了“催眠海绵”,一种充满芳香剂和麻醉剂的海绵,放在患者体内外科手术期间鼻子。[39] Ibn Zuhr(1091-1161)是Al-Andalus的另一位阿拉伯医生。在他12世纪的医学教科书Al-Taisir中,Ibn Zuhr描述了全身麻醉的使用。[引证需要]这三位医生是许多在吸入麻醉下使用麻醉浸泡的海绵进行手术的人之一。[40] [41]鸦片在10世纪到13世纪之间从小亚细亚到欧洲各地。[42]

在英国的公元1200 - 1500年间,一种名为dwale的药水被用作麻醉药。[43]这种以酒精为基础的混合物含有胆汁,鸦片,莴苣,苔藓植物,天仙子,铁杉和醋。[43]外科医生通过在颧骨上涂抹醋和盐来唤醒他们。[43]人们可以在众多文学资料中找到dwale的记录,包括莎士比亚的哈姆雷特和约翰济慈的诗“夜莺颂”。[43]在13世纪,我们有了第一个处方“海绵泡沫” - 浸泡在未成熟的桑椹,亚麻,曼陀罗叶,常春藤,莴苣种子,lapathum和带有hyoscyamus的铁杉的果汁中的海绵。在处理和/或储存后,海绵可以被加热并且吸入的蒸气具有美学效果。

炼金术士Ramon Llull在1275年发现了二乙醚。 [43] Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim(1493-1541),更为人所知的是Paracelsus,在1525年左右发现了二乙醚的镇痛特性。[44]它最初是由Valerius Cordus在1540年合成的,他注意到了它的一些药用特性。他称之为发烟硫酸矾,这个名字反映了它是通过蒸馏乙醇和硫酸的混合物合成的事实​​(已知)那时作为硫酸油)。奥古斯特·西蒙德·弗罗贝尼乌斯于1730年将这个名字命名为SpiritusViniÆthereus。[45] [46]

18世纪

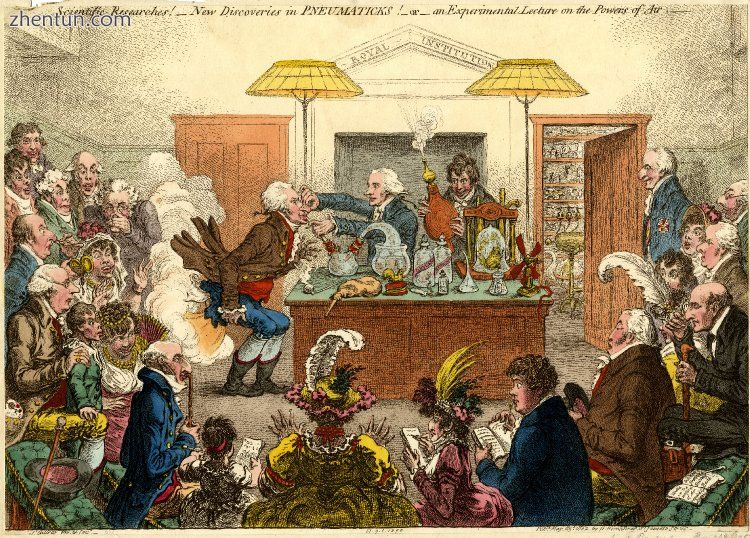

James Gillray的讽刺漫画展示了皇家机构的讲座,Humphry Davy拿着风箱和Count Rumford看着极右翼。

Joseph Priestley(1733-1804)是一名英国博学家,他发现了一氧化二氮,一氧化氮,氨,氯化氢和(以及Carl Wilhelm Scheele和Antoine Lavoisier)的氧气。从1775年开始,Priestley发表了他的研究“不同种类空气的实验和观察”,这是一部六卷的著作。[47]最近关于这些和其他气体的发现引起了欧洲科学界的极大兴趣。 Thomas Beddoes(1760-1808)是一位英国哲学家,医生和医学教师,和他年长的同事Priestley一样,也是伯明翰月球协会的成员。为了进一步推动这项新科学的发展以及为以前认为无法治愈的疾病(如哮喘和肺结核)提供治疗,Beddoes于1798年在布里斯托尔克利夫顿的道里广场成立了吸气治疗气动研究所。 [48] Beddoes聘请化学家和物理学家Humphry Davy(1778-1829)担任研究所主管,工程师James Watt(17​​36-1819)帮助制造气体。其他成员如Erasmus Darwin和Josiah Wedgwood也积极参与该研究所。

在他在气动研究所的研究过程中,戴维发现了一氧化二氮的麻醉特性。[49]戴维为氧化亚氮创造了“笑气”一词,第二年在现在的经典论文“化学和哲学研究”中发表了他的研究成果 - 主要涉及一氧化二氮或消炎的亚硝酸空气及其呼吸作用。戴维不是医生,他在手术过程中从未服用过氧化亚氮。然而,他是第一个记录氧化亚氮镇痛作用的人,以及它在减轻手术疼痛方面的潜在益处:[50]

由于氧化亚氮在其广泛的操作中似乎能够破坏身体疼痛,因此可能在外科手术期间有利地使用,其中不会发生大量血液渗出。

19世纪

东半球

据报道,来自Shuri,Ryūkyū王国的Takamine Tokumei于1689年在琉球(现称冲绳)进行全身麻醉。他于1690年将他的知识传授给了萨摩医生,并于1714年将他的知识传授给了Ryūkyūan医生。[51]

HanaokaSeishū,18和19世纪的日本外科医生

大阪的HanaokaSeishū(华冈青洲,1760-1835)是江户时代的日本外科医生,对中草药有所了解,以及他通过Rangaku学习的西方外科技术(字面意思是“荷兰学习”,并通过扩展“西方学习”)。从大约1785年开始,花冈开始寻求重新创造一种具有类似于华陀mafeisan的药理特性的化合物。[52]经过多年的研究和实验,他终于开发了一种名为tsūsensan(也称为mafutsu-san)的配方。与华o一样,这种化合物由几种不同植物的提取物组成,包括:[53] [54] [55]

2份白芝(中文:白芷,白芷);

2份cao wu(中文:草乌,乌头属植物,附子或狼人);

2份chuānbanxia(Pinellia ternata);

2份chuānxiōng(Ligusticum wallichii,Cnidium rhizome,Cnidium officinale或Szechuan lovage);

2份东菜(当归或雌人参);

1部分天南星(Arisaema rhizomatum或眼镜蛇百合)

8个部分杨金华(曼陀罗stramonium,韩国牵牛花,刺苹果,jimson杂草,魔鬼的小号,stinkweed,或locoweed)。

读者会注意到,这七种成分中的五种被认为是1600年前华佗麻醉药水的成分。一些消息来源声称Angelica archangelica(常被称为花园当归,圣灵,或野生芹菜)也是一种成分。

tsūsensan中的有效成分是东莨菪碱,莨菪碱,阿托品,乌头碱和天竺葵毒素。当消耗量足够时,tsūsensan会产生全身麻醉和骨骼肌麻痹状态。[55] Shuti Nakagawa(1773-1850)是Hanaoka的密友,于1796年写了一本名为“Mayaku-ko”(“麻醉粉”)的小册子。尽管原始手稿在1867年的一场大火中丢失,但这本小册子描述了当前Hanaoka对全身麻醉的研究。[56]

1804年10月13日,Hanaoka对一名名叫Kan Aiya的60岁女性进行了部分乳腺癌切除术,使用tsūsensan作为全身麻醉剂。今天通常认为这是在全身麻醉下进行手术的第一个可靠文件。[52] [54] [57] [58] Hanaoka继续使用tsūsensan进行许多手术,包括切除恶性肿瘤,拔除膀胱结石和肢体截肢。在他于1835年去世前,花冈进行了150多次乳腺癌手术。[52] [58] [59] [60]

西半球

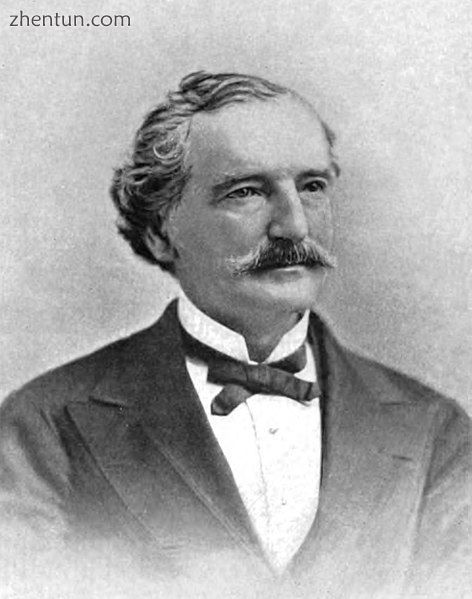

Gardner Quincy Colton,19世纪的美国牙医

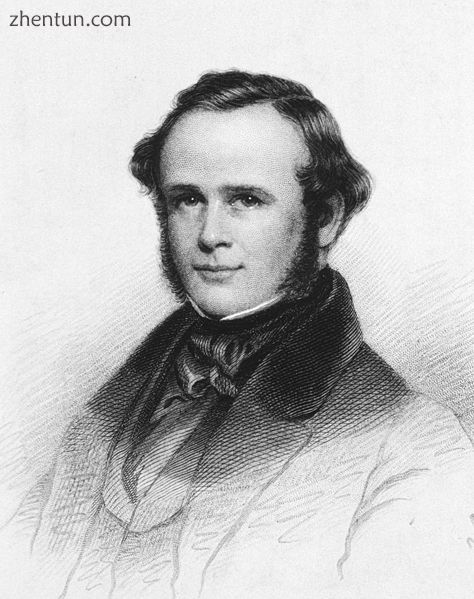

Horace Wells,19世纪的美国牙医

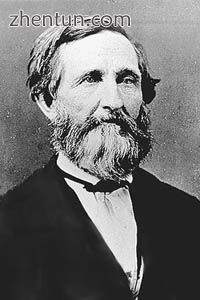

Crawford W. Long,19世纪的美国医生

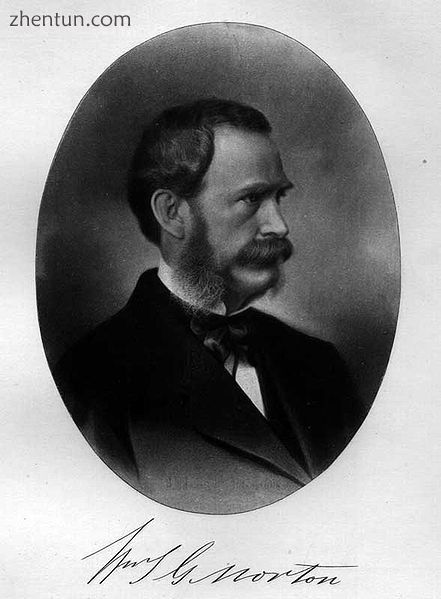

William T. G. Morton,19世纪的美国牙医

FriedrichSertürner(1783-1841)于1804年首次从鸦片中分离吗啡; [61]他将其命名为希腊梦之神Morpheus之后的吗啡。[62] [63]

Henry Hill Hickman(1800-1830)在19世纪20年代尝试使用二氧化碳作为麻醉剂。他会使动物感觉不敏感,有效地通过几乎窒息二氧化碳,然后通过切断其中一个肢体来确定气体的影响。 1824年,希克曼在一篇题为“关于假死的信件”的简短论文中向英国皇家学会提交了他的研究成果:旨在确定其在人类受试者外科手术中的可能效用。回应是1826年在“柳叶刀”上发表的题为“外科欺骗”的文章,该文章无情地批评了他的作品。希克曼四年后去世,享年30岁。尽管他在去世时并未受到重视,但他的工作得到了积极的重新评价,现在他被认为是麻醉之父。

到19世纪30年代后期,汉弗莱戴维的实验已在美国东北部的学术界广泛宣传。流浪的讲师将举行公众集会,称为“以太嬉戏”,鼓励观众吸入二乙醚或氧化亚氮,以展示这些代理人改变思维的特性,同时为旁观者提供更多娱乐。[64]四位著名的人参加了这些活动,目睹了以这种方式使用以太。他们是William Edward Clarke(1819-1898),Crawford W. Long(1815-1878),Horace Wells(1815-1848)和William T. G. Morton(1819-1868)。

1839年,在纽约罗切斯特大学本科学习期间,同学克拉克和莫顿显然参与了以太嬉戏,并且有规律。[65] [66] [67] [68] 1842年1月,现在是伯克希尔医学院的一名医学院学生,克拉克为一位霍比小姐管理了以太,而以利亚教皇则进行了拔牙。[66]通过这样做,他成为第一个使用吸入麻醉剂以促进外科手术的表现的人。克拉克显然没有想到他的成就,并且既没有发表也没有选择继续这种技术。事实上,在克拉克的传记中甚至没有提到这个事件。[69]

Crawford W. Long是19世纪中叶在乔治亚州杰斐逊市执业的医生和药剂师。在19世纪30年代后期作为宾夕法尼亚大学医学院的学生期间,他观察并且可能参与了当时流行的以太嬉戏。在这些聚会上,Long观察到一些参与者经历了颠簸和瘀伤,但后来却没有回忆起发生的事情。他假定二乙醚产生类似于氧化亚氮的药理作用。 1842年3月30日,他吸入二乙醚给一名名叫James Venable的男子,以便从男人的脖子上清除肿瘤。[70]很久以后,再次在乙醚麻醉下从Venable移除了第二个肿瘤。他继续使用乙醚作为肢体截肢和分娩的全身麻醉剂。然而,很长一段时间没有公布他的经历直到1849年,从而否定了他应得的大部分功劳。[70]

随着现代医学的开始,为医生和外科医生设定了一个阶段,以建立麻醉变得有用的范例[71]。

1844年12月10日,Gardner Quincy Colton在康涅狄格州哈特福德市举行了一氧化二氮的公开示威活动。其中一名参赛者塞缪尔·库利(Samuel A. Cooley)在受到氧化亚氮影响的情况下腿部严重受伤而没有注意到受伤情况。当天在观众中出席的康涅狄格州牙医霍勒斯威尔斯立即抓住了这种明显的氧化亚氮镇痛作用的重要性。第二天,Wells在Colton施用的一氧化二氮的影响下进行了无痛的拔牙。 Wells随后开始给患者服用一氧化二氮,并在接下来的几周内成功进行了几次牙科拔牙。

威廉·T·莫顿(William T. G. Morton)是另一位新英格兰牙医,曾是威尔斯的学生和当时的商业伙伴。他也是William Edward Clarke的前熟人和同学(两人曾在纽约罗切斯特一起上过本科学校)。 Morton安排Wells在著名的外科医生John Collins Warren的陪同下,在麻省总医院的氧化亚氮全身麻醉下展示他的拔牙技术。这次演示于1845年1月20日举行,当病人在手术中途痛苦地哭泣时结束了。[72]

1846年9月30日,莫顿给来自波士顿的音乐老师Eben Frost提供了二乙醚用于拔牙。两周后,莫顿成为第一个公开证明在马萨诸塞州综合医院使用二乙醚作为全身麻醉剂的人,现在称为以太圆顶。[73] 1846年10月16日,约翰·柯林斯·沃伦从当地印刷商爱德华·吉尔伯特·阿博特的脖子上取下了一个肿瘤。据报道,在完成手术后,沃伦打趣说:“先生们,这不是骗子。”这一事件的消息迅速传遍全世界。[74]罗伯特利斯顿于当年12月进行了第一次截肢。莫顿很快就发表了他的经历。[73]哈佛大学教授查尔斯托马斯杰克逊(1805-1880)后来声称莫顿偷走了他的想法; [75]莫顿不同意并开始终身争执。[74]多年来,Morton被认为是西半球全身麻醉的先驱,尽管他的示范发生在Long的初步经历四年之后。很久以后请求当时来自格鲁吉亚的美国参议员威廉·克罗斯比·道森(1798-1856),支持他在美国参议院作为第一个使用乙醚麻醉的人的要求。[76]

1847年,爱丁堡的苏格兰产科医生詹姆斯杨辛普森(1811-1870)是第一个使用氯仿作为人类全身麻醉剂的人(罗伯特莫蒂默格洛弗在1842年写过这种可能性,但只用于狗)。此后在欧洲,氯仿麻醉的使用迅速扩大。在20世纪初,氯仿开始在美国取代乙醚作为麻醉剂。当它的肝脏和心脏毒性,尤其是导致潜在致命性心律失常的倾向变得明显时,它很快就被放弃了以太有利于乙醚。事实上,氯仿与乙醚作为主要麻醉气体的用途因国家和地区而异。例如,英国和美国南部坚持使用氯仿,而美国北部则回归以太[71]。约翰斯诺迅速成为最有经验的英国医生,使用新的乙醚和氯仿麻醉气体,从而成为第一位英国麻醉师。通过他精心的临床记录,他最终能够说服伦敦医学精英认为麻醉(氯仿)在分娩时具有合法的地位。因此,1853年维多利亚女王的陪同人员邀请约翰·斯诺为女王的第八个孩子的出生麻醉[77]。从乙醚和氯仿麻醉开始直到20世纪,标准的给药方法是滴剂。将面罩放在患者口腔上,其中含有一些织物,并且挥发性液体滴在面罩上,患者自发呼吸。后来安全气管导管的发展改变了这一点[78]。由于伦敦医学独特的社会环境,到19世纪末,麻醉已经成为它自己的专长,而在英国其他地区和世界大部分地区,麻醉仍属于外科医生的职权范围。任务给初级医生或护士[71]。

奥地利外交官Karl von Scherzer从秘鲁带回了足量的可可叶后,1860年Albert Niemann分离出可卡因,因此成为第一种局部麻醉剂。[79] [80]

1871年,德国外科医生弗里德里希特伦德伦堡(1844-1924)发表了一篇论文,描述了第一次成功进行选择性人体气管切开术,以便进行全身麻醉。[81] [82] [83] [84]

1880年,苏格兰外科医生William Macewen(1848-1924)报道了他使用经口气管插管作为气管切开术的替代方法,以使患有声门水肿的患者能够呼吸,以及使用氯仿进行全身麻醉。[85] [86] [87]所有先前对声门和喉部的观察(包括ManuelGarcía,[88] Wilhelm Hack [89] [90]和Macewen)都是在间接视觉下(使用镜子)进行的,直到1895年4月23日Alfred Kirstein(1863- 1922年德国首次描述了声带的直接可视化。 Kirstein在柏林进行了第一次直接喉镜检查,使用他为此目的修改的食道镜;他把这个设备称为一个验尸仪。[91]皇帝弗雷德里克三世(1831-1888)[92]的死亡可能促使基尔斯坦开发了验尸仪。[93]

20世纪

Hermann Emil Fischer,德国化学家

20世纪,气管切开术,内窥镜检查和非手术气管插管的实践从极少使用的手术转变为麻醉,重症监护医学,急诊医学,胃肠病学,肺病学和外科手术的基本组成部分。

1902年,Hermann Emil Fischer(1852-1919)和Joseph von Mering(1849-1908)发现二乙基巴比妥酸是一种有效的催眠药。[94]这种新药也被称为barbital或Veronal(拜耳制药公司指定的商品名),成为第一个商业销售的巴比妥酸盐;从1903年到20世纪50年代中期,它被用作治疗失眠症。

直到1913年,口腔和颌面外科手术通过面罩吸入麻醉,局部麻醉剂局部应用于粘膜,直肠麻醉或静脉麻醉进行。虽然有效,但这些技术不能保护气道免受阻塞,并且还使患者暴露于肺部吸入血液和粘液进入气管支气管系统的风险。 1913年,Chevalier Jackson(1865-1958)是第一个报告使用直接喉镜作为插管气管的手段的成功率很高的人。[95]杰克逊推出了一种新的喉镜刀片,在远端尖端有一个光源,而不是基尔斯坦使用的近端光源。[96]这种新型刀片包含一个部件,操作员可以将其滑出,以便为气管导管或支气管镜通过提供空间。[97]

同样在1913年,Henry H. Janeway(1873-1921)公布了他最近使用喉镜实现的结果。[98] Janeway是一位在纽约市Bellevue医院执业的美国麻醉师,他认为直接气管内注入挥发性麻醉剂可以为耳鼻喉科手术提供更好的条件。考虑到这一点,他开发了一种专为气管插管而设计的喉镜。与Jackson的设备类似,Janeway的仪器包含远端光源。然而,独特的是在手柄内包含电池,刀片中的中央凹口用于在插管期间将气管导管保持在口咽中线,并且与刀片的远端尖端略微弯曲以帮助引导导管穿过声门。这种设计的成功导致其随后用于其他类型的手术。因此,Janeway在推广麻醉学实践中广泛使用直接喉镜和气管插管方面发挥了重要作用。[93]

1928年,亚瑟·欧内斯特·盖德尔(Arthur Ernest Guedel)介绍了带袖套的气管导管,这种麻醉可以完全抑制自发呼吸,同时通过麻醉师控制的正压通气输送气体和氧气[99]。麻醉机也是进口现代麻醉的开发。仅仅三年后,盖尔开发出了一种技术,麻醉师一次只能通气一肺[100]。允许胸外科手术的发展,这种手术以前一直被pendulluft [101]问题所困扰,在这个问题中,由于胸腔向大气开放而失去真空,导致患者呼气时肺部受到充气。最终到了20世纪80年代早期,双腔气管插管由透明塑料制成,使麻醉师能够选择性通气,同时使用柔性纤维支气管镜检查来阻断患病肺部并防止交叉污染[78]。一个早期的设备,铜壶,是由威斯康星大学的Lucien E. Morris博士开发的。[102] [103]

硫喷妥钠是第一种静脉麻醉药,于1934年由Ernest H. Volwiler(1893-1992)和Donalee L. Tabern(1900-1974)合成,为Abbott Laboratories工作。[104]它于1934年3月8日由Ralph M. Waters首次用于人类,研究其性质,即短期麻醉和令人惊讶的镇痛效果。三个月后,John Silas Lundy应雅培实验室的要求,在梅奥诊所开始了硫喷妥钠的临床试验。 Volwiler和Tabern于1939年因发现硫喷妥钠而获得美国专利2,153,729,并于1986年入选国家发明家名人堂。

1939年,寻找阿托品的合成替代品,偶然发现了哌替啶,这是第一种具有与吗啡完全不同的结构的鸦片制剂。[105]随后于1947年广泛引入了美沙酮,这是另一种结构不相关的化合物,具有与吗啡类似的药理学特性。[106]

第一次世界大战后,在气管内麻醉领域取得了进一步的进展。其中包括Ivan Whiteside Magill爵士(1888-1986)制作的那些。通过整形外科医生Harold Gillies爵士(1882-1960)和麻醉师E. Stanley Rowbotham(1890-1979)在Sidcup的女王医院进行面部和颌骨损伤,Magill开发了清醒盲鼻气管插管技术。[107] [108] ] [109] [110] [111] [112] Magill设计了一种新型的角形钳(Magill镊子),目前仍用于促进鼻气管插管,其方式与Magill的原始技术相比几乎没有变化。[113] Magill发明的其他装置包括Magill喉镜刀片,[114]以及几种挥发性麻醉剂给药装置。[115] [116] [117]气管导管的Magill曲线也以Magill命名。

第一家医院麻醉科于1936年在Henry K. Beecher(1904-1976)的领导下在马萨诸塞州总医院成立。 Beecher接受过外科手术训练,之前没有麻醉经验。[118]

虽然最初用于减少与精神疾病的电击疗法相关的痉挛性变性,但是在20世纪40年代,使用Squibb [119]制备的制剂,在E.v. Papper和Stuart Cullen的手术室中使用了curare。这种神经肌肉阻滞使膈肌完全麻痹,并通过正压通气控制通气[78]。机械通气首先成为20世纪50年代脊髓灰质炎流行病的常见地方,最明显的是在丹麦,1952年爆发导致麻醉期间产生重症监护医学。在第一次麻醉医生处于犹豫不决的情况下,除非必要,否则将呼吸机带入手术室,但到了20世纪60年代,它成为了标准的手术室设备[78]。

Sir Robert Reynolds Macintosh(1897-1989)在1943年推出新的弯曲喉镜刀片时,在气管插管技术方面取得了重大进展。[120] Macintosh刀片至今仍是用于经口气管插管的最广泛使用的喉镜刀片。[121] 1949年,Macintosh发表了一份病例报告,描述了弹性导尿管作为气管插管引入器的新用途,以促进气管插管困难。[122]受Macintosh报告的启发,P. Hex Venn(当时是英国公司Eschmann Bros.&Walsh,Ltd。的麻醉顾问)着手开发一种基于这一概念的气管插管导引器。维恩的设计在1973年3月被接受,而后来被称为埃施曼气管导管的人在那年晚些时候投入生产。[123]维恩设计的材料与胶弹性探针的材料不同,它具有两层:由聚酯线编织的管芯和外树脂层。这提供了更大的刚度,但保持了柔韧性和光滑的表面。其他差异是长度(新的导入器是60厘米(24英寸),比胶弹性探针长得多)和35°弯曲尖端的存在,允许它在障碍物周围转向。[124] [125] ]

一百多年来,吸入麻醉药的主要支柱仍然是环氧丙烷醚,这种环丙烷是在20世纪30年代引入的。 1956年引入了氟烷[126],其具有不易燃的显著优点。这降低了手术室火灾的风险。在六十年代,由于心律失常和肝脏毒性的罕见但显著的副作用,卤代醚取代了氟烷。前两种卤代醚是甲氧氟烷和安氟醚。这些反过来被八十年代和九十年代的异氟醚,七氟醚和地氟醚的现行标准所取代,尽管甲氧氟烷在澳大利亚作为Penthrox用于院前麻醉。在大多数发展中国家,氟烷仍然存在。

许多新的静脉注射和吸入麻醉剂在20世纪下半叶开发并投入临床使用。 Janssen Pharmaceutica的创始人Paul Janssen(1926-2003)因开发了80多种药物而受到赞誉。[127] Janssen合成了几乎所有的丁酰苯类抗精神病药,从氟哌啶醇(1958)和氟哌利多(1961)开始。[128]这些药物迅速融入麻醉实践中。[129] [130] [131] [132] [133] 1960年,Janssen的团队合成了芬太尼,这是第一种哌啶酮衍生的阿片类药物。[134] [135]芬太尼之后是舒芬太尼(1974),[136]阿芬太尼(1976),[137] [138]卡芬太尼(1976),[139]和lofentanil(1980)。[140] Janssen和他的团队还开发了依托咪酯(1964),[141] [142]一种有效的静脉麻醉诱导剂。

1967年,英国麻醉师Peter Murphy介绍了使用光纤内窥镜进行气管插管的概念。[143]到20世纪80年代中期,柔性纤维支气管镜已成为肺病学和麻醉学界不可或缺的工具。[144]

21世纪

现代麻醉机。 这种特殊的机器是由Maquet制造的“Flow-I”型号。

21世纪的“数字革命”为气管插管的艺术和科学带来了更新的技术。 一些制造商已经开发出视频喉镜,其采用诸如互补金属氧化物半导体有源像素传感器(CMOS APS)之类的数字技术来产生声门的视图,从而可以插管气管。 Glidescope视频喉镜就是这种设备的一个例子。[145] [146]

氙气最近在某些司法管辖区被批准为不作为温室气体的麻醉剂。[147]

另见

History portal

icon Medicine portal

A.C.E. mixture

American Association of Nurse Anesthetists

American Society of Anesthesiologists

Arthur Ernest Guedel

ASA physical status classification system

Blood transfusion

Boyle's machine

Curare

Fidel Pagés

Henry Edmund Gaskin Boyle

History of anatomy

History of medicine

History of neuraxial anesthesia

History of neuroscience

History of surgery

History of tracheal intubation

James Esdaile

John Snow (physician)

Joseph Thomas Clover

Local anesthesia

Royal College of Anaesthetists

Takamine Tokumei

Walter Channing

The Zoist: A Journal of Cerebral Physiology & Mesmerism, and Their Applications to Human Welfare

参考:

Kuntz, L; Vera, A (July – September 2005). "Transfer pricing in hospitals and efficiency of physicians: the case of anesthesia services". Health Care Management Review. 30 (3): 262–69. doi:10.1097/00004010-200507000-00010. PMID 16093892.

Small, MR (1962). Oliver Wendell Holmes. New York: Twayne Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8084-0237-4. OCLC 273508. In a letter to dentist William T. G. Morton, Holmes wrote: "Everybody wants to have a hand in a great discovery. All I will do is to give a hint or two as to names—or the name—to be applied to the state produced and the agent. The state should, I think, be called 'Anaesthesia.' This signifies insensibility—more particularly ... to objects of touch."

Powell MA (2004). "9: Wine and the vine in ancient Mesopotamia: the cuneiform evidence". In McGovern PE, Fleming SJ, Katz SH (eds.). The Origins and Ancient History of Wine. Food and Nutrition in History and Anthropology. 11 (1 ed.). Amsterdam: Taylor & Francis. pp. 96–124. ISBN 9780203392836. ISSN 0275-5769. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

Evans, TC (1928). "The opium question, with special reference to Persia (book review)". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 21 (4): 339–340. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(28)90031-0. Retrieved 18 September 2010. The earliest known mention of the poppy is in the language of the Sumerians, a non-Semitic people who descended from the uplands of Central Asia into Southern Mesopotamia....[permanent dead link]

Booth M (1996). "The discovery of dreams". Opium: A History. London: Simon & Schuster, Ltd. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-312-20667-3. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Krikorian, AD (March 1975). "Were the opium poppy and opium known in the ancient Near East?". Journal of the History of Biology. 8 (1): 95–114. doi:10.1007/BF00129597. PMID 11609871.

Kramer, SN (March 1954). "First pharmacopeia in man's recorded history". American Journal of Pharmacy and the Sciences Supporting Public Health. 126 (3): 76–84. ISSN 0002-9467. PMID 13148318.

Kramer SN, Tanaka H (March 1988). History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Recorded History (3 ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1276-1.

Terry CE, Pellens M (1928). "II: Development of the problem". The Opium Problem. New York: Bureau of Social Hygiene. p. 54. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Sonnedecker G (1962). "Emergence of the Concept of Opiate Addiction". Journal Mondial de Pharmacie. 3: 275–290. ISSN 0021-8405.

Anslinger HJ, Tompkins WF (1953). "The pattern of man's use of narcotic drugs". The Traffic in Narcotics. New York: Funk and Wagnalls. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-405-13567-5. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Thompson RC (July 1926). "The Assyrian herbal: a monograph on the Assyrian vegetable drugs". Isis. 8 (3): 506–508. doi:10.1086/358424. JSTOR 223920. Thompson reinforces his view with the following quotation from a cuneiform tablet: 'Early in the morning old women, boys and girls collect the juice, scraping it off the notches (of the poppy-capsule) with a small iron blade, and place it within a clay receptacle.'

Ludwig Christian Stern (1889). Ebers G (ed.). Papyrus Ebers (in German). 2 (1 ed.). Leipzig: Bei S. Hirzel. OCLC 14785083. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Pahor, AL (August 1992). "Ear, nose and throat in ancient Egypt: Part I". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 106 (8): 677–87. doi:10.1017/S0022215100120560. PMID 1402355.

Sullivan, R (August 1996). "The identity and work of the ancient Egyptian surgeon". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 89 (8): 467–73. doi:10.1177/014107689608900813. PMC 1295891. PMID 8795503.

Ebbell B (1937). The Papyrus Ebers: The greatest Egyptian medical document. Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard. Archived from the original on 26 February 2005. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Bisset NG, Bruhn JG, Curto S, Halmsted B, Nymen U, Zink MH (January 1994). "Was opium known in 18th Dynasty ancient Egypt? An examination of materials from the tomb of the chief royal architect Kha". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 41 (1–2): 99–114. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(94)90064-7. PMID 8170167.

Kritikos PG, Papadaki SP (1967). "The history of the poppy and of opium and their expansion in antiquity in the eastern Mediterranean area". Bulletin on Narcotics. 19 (3): 17–38. ISSN 0007-523X. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Sushruta (1907). "Introduction". In Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna (ed.). Sushruta Samhita, Volume1: Sutrasthanam. Calcutta: Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna. pp. iv. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Dwarakanath SC (1965). "Use of opium and cannabis in the traditional systems of medicine in India". Bulletin on Narcotics. 17 (1): 15–9. ISSN 0007-523X. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

Fort J (1965). "Giver of delight or Liberator of sin: Drug use and "addiction" in Asia". Bulletin on Narcotics. 17 (3): 1–11. ISSN 0007-523X. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

Gordon BL (1949). Medicine throughout Antiquity (1 ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. pp. 358, 379, 385, 387. OCLC 1574261. Retrieved 14 September 2010. Pien Chiao (ca. 300 BC) used general anesthesia for surgical procedures. It is recorded that he gave two men, named "Lu" and "Chao", a toxic drink which rendered them unconscious for three days, during which time he performed a gastrotomy upon them

Giles L (transl.) (1912). Taoist teachings from the book of Lieh-Tzŭ, translated from the Chinese, with introduction and notes, by Lionel Giles (Wisdom of the East series). London: John Murray. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

Salguero, CP (February 2009). "The Buddhist medicine king in literary context: reconsidering an early medieval example of Indian influence on Chinese medicine and surgery" (PDF). History of Religions. 48 (3): 183–210. doi:10.1086/598230. ISSN 0018-2710. Retrieved 14 September 2010.[permanent dead link]

Chu NS (December 2004). "Legendary Hwa Tuo's surgery under general anesthesia in the second century China" (PDF). Acta Neurologica Taiwanica (in Chinese). 13 (4): 211–6. ISSN 1028-768X. PMID 15666698. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Giles HA (1898). A Chinese Biographical Dictionary. London: Bernard Quaritch. pp. 323–4, 762–3. Retrieved 14 September 2010. If a disease seemed beyond the reach of needles and cautery, he operated, giving his patients a dose of hashish which rendered them unconscious.

Giles L (transl.) (1948). Cranmer-Byng JL (ed.). A Gallery of Chinese immortals: selected biographies, translated from Chinese sources by Lionel Giles (Wisdom of the East series) (1 ed.). London: John Murray. Retrieved 14 September 2010. The well-attested fact that Hua T'o made use of an anaesthetic for surgical operations over 1,600 years before Sir James Simpson certainly places him to our eyes on a pinnacle of fame....

Chen J (August 2008). "A Brief Biography of Hua Tuo". Acupuncture Today. 9 (8). ISSN 1526-7784. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Wang Z; Ping C (1999). "Well-known medical scientists: Hua Tuo". In Ping C (ed.). History and Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 1. Beijing: Science Press. pp. 88–93. ISBN 978-7-03-006567-4. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Fu LK (August 2002). "Hua Tuo, the Chinese god of surgery". Journal of Medical Biography. 10 (3): 160–6. doi:10.1177/096777200201000310. PMID 12114950. Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Huang Ti Nei Ching Su Wen: The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine. Translated by Ilza Veith. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1972. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-520-02158-7.

Ch'en S (2000). "The Biography of Hua-t'o from the History of the Three Kingdoms". In Mair VH (ed.). The shorter Columbia anthology of traditional Chinese literature. Part III: Prose. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 441–9. ISBN 978-0-231-11998-6. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Lu GD; Needham J (2002). "Acupuncture and major surgery". Celestial lancets: a history and rationale of acupuncture and moxa. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 218–30. ISBN 978-0-7007-1458-2. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Wai, FK (2004). "On Hua Tuo's Position in the History of Chinese Medicine". The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 32 (2): 313–20. doi:10.1142/S0192415X04001965. PMID 15315268.

Carroll E. (1997). "Coca: the plant and its use" (PDF). In Robert C. Petersen; Richard C. Stillman (eds.). Cocaine: 1977. United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. p. 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

Peterson, RC (1997). "History of Cocaine" (PDF). In Robert C. Petersen; Richard C. Stillman (eds.). Cocaine: 1977. United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. pp. 17–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

Rivera MA; Aufderheide AC; Cartmell LW; Torres CM; Langsjoen O (December 2005). "Antiquity of coca-leaf chewing in the south central Andes: a 3,000 year archaeological record of coca-leaf chewing from northern Chile". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 37 (4): 455–8. doi:10.1080/02791072.2005.10399820. PMID 16480174.

Ahmad, Z. (St Thomas' Hospital) (2007), "Al-Zahrawi - The Father of Surgery", ANZ Journal of Surgery, 77 (Suppl. 1): A83, doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04130_8.x

Skinner, P (2008). "Unani-tibbi". In Laurie J. Fundukian (ed.). The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine (3rd ed.). Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale Cengage. ISBN 978-1-4144-4872-5. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Ajram K (1992). Miracle of Islamic Science (1 ed.). Vernon Hills, IL: Knowledge House Publishers. pp. Appendix B. ISBN 978-0-911119-43-5. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Hunke S (1960). Allahs Sonne über dem Abendland: unser arabisches Erbe (in German) (2 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. pp. 279–80. ISBN 978-3-596-23543-8. Retrieved 13 September 2010. The science of medicine has gained a great and extremely important discovery and that is the use of general anaesthetics for surgical operations, and how unique, efficient, and merciful for those who tried it the Muslim anaesthetic was. It was quite different from the drinks the Indians, Romans and Greeks were forcing their patients to have for relief of pain. There had been some allegations to credit this discovery to an Italian or to an Alexandrian, but the truth is and history proves that, the art of using the anaesthetic sponge is a pure Muslim technique, which was not known before. The sponge used to be dipped and left in a mixture prepared from cannabis, opium, hyoscyamus and a plant called Zoan.

Kritikos PG, Papadaki SP (1967). "The History of the Poppy and of Opium and Their Expansion in Antiquity in the Eastern Mediterranean Area". Bulletin on Narcotics. 19 (4): 5–10. ISSN 0007-523X.

Carter, Anthony J. (18 December 1999). "Dwale: an anaesthetic from old England". BMJ. 319 (7225): 1623–1626. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1623. PMC 1127089. PMID 10600971.

Gravenstein JS (November – December 1965). "Paracelsus and his contributions to anesthesia". Anesthesiology. 26 (6): 805–11. doi:10.1097/00000542-196511000-00016. PMID 5320896. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

Frobenius, AS (1 January 1729). "An Account of a Spiritus Vini Æthereus, Together with Several Experiments Tried Therewith". Philosophical Transactions. 36 (413): 283–9. doi:10.1098/rstl.1729.0045.[permanent dead link]

Mortimer, C; Mortimer, C. (1 January 1739). "Abstracts of the Original Papers Communicated to the Royal Society by Sigismond Augustus Frobenius, M. D. concerning His Spiritus Vini Aethereus: Collected by C. Mortimer, M. D. Secr. R. S". Philosophical Transactions. 41 (461): 864–70. doi:10.1098/rstl.1739.0161.[permanent dead link]

Priestley J (1775). Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air. 1 (2 ed.). London: J. Johnson. pp. 108–29, 203–29. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Levere, TH (July 1977). "Dr. Thomas Beddoes and the establishment of his Pneumatic Institution: a tale of three presidents". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 32 (1): 41–9. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1977.0005. JSTOR 531764. PMID 11615622.

Sneader W (2005). "Chapter 8: Systematic medicine". Drug discovery: a history. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 78–9. ISBN 978-0-471-89980-8. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Davy H (1800). Researches, chemical and philosophical–chiefly concerning nitrous oxide or dephlogisticated nitrous air, and its respiration. Bristol: Biggs and Cottle. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Arashiro Toshiaki, Ryukyu-Okinawa Rekishi Jinbutusuden OkinawaJijishuppan, 12006. pp. 66–68

Izuo, M (November 2004). "Medical history: Seishū Hanaoka and his success in breast cancer surgery under general anesthesia two hundred years ago". Breast Cancer. 11 (4): 319–24. doi:10.1007/BF02968037. PMID 15604985.

Ogata T (November 1973). "Seishu Hanaoka and his anaesthesiology and surgery". Anaesthesia. 28 (6): 645–52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1973.tb00549.x. PMID 4586362.

Hyodo M (1992). "Doctor S. Hanaoka, the world's-first success in providing general anesthesia". In Hyodo M, Oyama T, Swerdlow M (eds.). The Pain Clinic IV: proceedings of the fourth international symposium. Utrecht, Netherlands: VSP. pp. 3–12. ISBN 978-90-6764-147-0. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

van D., JH (2010). "Chosen-asagao and the recipe for Hanaoka's anesthetic 'tsusensan'". Brighton, UK: BLTC Research. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Matsuki A (December 1999). "A bibliographical study on Shutei Nakagawa's "Mayaku-ko" (a collection of anesthetics and analgesics)--a comparism of four manuscripts". Nihon Ishigaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 45 (4): 585–99. ISSN 0549-3323. PMID 11624281. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Perrin, N (1979). Giving up the gun: Japan's reversion to the sword, 1543–1879. Boston: David R. Godine. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-87923-773-8. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Matsuki A (September 2000). "New studies on the history of anesthesiology--a new study on Seishū Hanaoka's "Nyugan Ckiken Roku" (a surgical experience with breast cancer)". Masui. 49 (9): 1038–43. ISSN 0021-4892. PMID 11025965. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Tominaga, T (30 December 1994). "Presidential address: Newly established Japanese breast cancer society and the future". Breast Cancer. 1 (2): 69–78. doi:10.1007/BF02967035. PMID 11091513.

Matsuki A (March 2002). "A Study on Seishu Hanaoka's Nyugan Seimei Roku (Scroll of Diseases): A Name List of Breast Cancer Patients". Nihon Ishigaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 48 (1): 53–65. ISSN 0549-3323. PMID 12152628. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Meyer, K (2004). "Dem Morphin auf der Spur". Pharmazeutischen Zeitung (in German). GOVI-Verlag. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

Serturner FWA (1806). J. Pharm. f. Arzte. Apoth. Chem. 14, 47–93.

Serturner FWA (1817). Gilbert's Annalen der Physik 25, 56–89.

Desai SP, Desai MS, Pandav CS (2007). "The discovery of modern anaesthesia-contributions of Davy, Clarke, Long, Wells and Morton". Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 51 (6): 472–8. ISSN 0019-5049. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Sims JM (1877). "The Discovery of Anaesthesia". Virginia Medical Monthly. 4 (2): 81–100.

Lyman HM (1881). "History of anaesthesia". Artificial anaesthesia and anaesthetics. New York: William Wood and Company. p. 6. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Lyman HM (September 1886). "The discovery of anesthesia". Virginia Medical Monthly. 13 (6): 369–92. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Richmond PA (1950). "Was William E. Clarke of Rochester the first American to use ether for surgical anesthesia?". Genessee County Scrapbook of the Rochester Historical Society. 1: 11–3.

Stone RF (1898). Stone RF (ed.). Biography of Eminent American Physicians and Surgeons (2 ed.). Indianapolis: CE Hollenbeck. p. 89. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Long CW (December 1849). "An account of the first use of Sulphuric Ether by Inhalation as an Anaesthetic in Surgical Operations". Southern Medical and Surgical Journal. 5: 705–13. reprinted in Long, C. W. (December 1991). "An account of the first use of Sulphuric Ether by Inhalation as an Anaesthetic in Surgical Operations". Survey of Anesthesiology. 35 (6): 375. doi:10.1097/00132586-199112000-00049.

Snow, Stephanie (2005). Operations without pain: the practice and science of anaesthesia in Victorian Britain. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-333-71492-8.

Wells, H (1847). A History of the Discovery of the Application of Nitrous Oxide Gas, Ether, and Other Vapors to Surgical Operations. Hartford: J. Gaylord Wells. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Morton, WTG (1847). Remarks on the Proper Mode of Administering Sulphuric Ether by Inhalation (PDF). Boston: Button and Wentworth. OCLC 14825070. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Fenster, JM (2001). Ether Day: The Strange Tale of America's Greatest Medical Discovery and the Haunted Men Who Made It. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019523-6.

Jackson CT (1861). A Manual of Etherization: Containing Directions for the Employment of Ether. Boston: J.B. Mansfield. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Northen WJ; Graves JT (1910). Men of Mark in Georgia: A Complete and Elaborate History of the State from Its Settlement to the Present Time, Chiefly Told in Biographies and Autobiographies of the Most Eminent Men of Each Period of Georgia's Progress and Development. 2. Atlanta, Georgia: A.B. Caldwell. pp. 131–136.

Caton, D (2000). "John Snow's practice of obstetric anesthesia". Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 92 (1): 247–52. PMID 10638922.

Brodsky, J; Lemmens, H (2007). "The history of anesthesia for thoracic surgery". Minerva Anestesiologica. 73 (10): 513–24. PMID 17380101.

Wawersik, J (May – June 1991). "History of anesthesia in Germany". Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 3 (3): 235–244. doi:10.1016/0952-8180(91)90167-L. PMID 1878238. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Bain, JA; Spoerel, WE (November 1964). "Observation on the use of cuffed tracheostomy tubes (with particular reference to the James tube)". Canadian Anaesthetists' Society Journal. 11 (6): 598–608. doi:10.1007/BF03004104. PMID 14232175.

Trendelenburg, F (1871). "Beiträge zu den Operationen an den Luftwegen" [Contributions to airways surgery]. Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie (in German). 12: 112–33.

Hargrave, R (June 1934). "Endotracheal Anæsthesia in Surgery of the Head and Neck". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 30 (6): 633–7. PMC 403396. PMID 20319535.

Reutsch, Y; Boni, T; Borgeat, A (2001). "From cocaine to ropivacaine: the history of local anesthetic drugs". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 1 (3): 175–182. doi:10.2174/1568026013395335. PMID 11895133.

Niemann, A (1860). "Uber eine Neue Organische Base in den Cocablättern [thesis]". Göttingen.

Macewen, W (July 1880). "General Observations on the Introduction of Tracheal Tubes by the Mouth, Instead of Performing Tracheotomy or Laryngotomy". British Medical Journal. 2 (1021): 122–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1021.122. PMC 2241154. PMID 20749630.

Macewen, W (July 1880). "Clinical Observations on the Introduction of Tracheal Tubes by the Mouth, Instead of Performing Tracheotomy or Laryngotomy". British Medical Journal. 2 (1022): 163–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1022.163. PMC 2241109. PMID 20749636.

Macmillan, M (May 2010). "William Macewen [1848–1924]". Journal of Neurology. 257 (5): 858–9. doi:10.1007/s00415-010-5524-5. PMID 20306068.

García, M (24 May 1855). "Observations on the Human Voice". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 7: 399–410. doi:10.1098/rspl.1854.0094. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Hack, W (1878). "über die mechanische Behandlung der Larynxstenosen" [On the mechanical treatment of laryngeal stenosis]. Sammlung Klinischer Vorträge (in German). 152: 52–75.

Hack, W (March 1878). "über einen fall endolaryngealer exstirpation eines polypen der vorderen commissur während der inspirationspause". Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift (in German): 135–7. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Hirsch, NP; Smith, GB; Hirsch, PO (January 1986). "Alfred Kirstein. Pioneer of direct laryngoscopy". Anaesthesia. 41 (1): 42–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1986.tb12702.x. PMID 3511764.

Mackenzie, M (1888). The case of Emperor Frederick III.: full official reports by the German physicians and by Sir Morell Mackenzie. New York: Edgar S. Werner. p. 276. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Burkle, CM; Zepeda, FA; Bacon, DR; Rose, SH (April 2004). "A historical perspective on use of the laryngoscope as a tool in anesthesiology". Anesthesiology. 100 (4): 1003–6. doi:10.1097/00000542-200404000-00034. PMID 15087639.

Fischer EH; Mering J (March 1903). "Ueber eine neue Klasse von Schlafmitteln". Die Therapie der Gegenwart (in German). 5: 97–101. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Jackson, C (1913). "The technique of insertion of intratracheal insufflation tubes". Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 17: 507–9. Reprinted in Jackson, Chevalier (May 1996). "The technique of insertion of intratracheal insufflation tubes". Pediatric Anesthesia. 6 (3): 230. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.1996.tb00434.x.

Zeitels, S (March 1998). "Chevalier Jackson's contributions to direct laryngoscopy". Journal of Voice. 12 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S0892-1997(98)80069-6. PMID 9619973.

Jackson, C (1922). "I: Instrumentarium" (PDF). A manual of peroral endoscopy and laryngeal surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 17–52. ISBN 978-1-4326-6305-6. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Janeway, HH (November 1913). "Intra-tracheal anesthesia from the standpoint of the nose, throat and oral surgeon with a description of a new instrument for catheterizing the trachea". The Laryngoscope. 23 (11): 1082–90. doi:10.1288/00005537-191311000-00009.

Guedel, A; Waters, R (1928). "A new intratracheal catheter". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 7 (4): 238–239.

Gale, J; Waters, R (1932). "Closed endobronchial anesthesia in thoracic surgery: preliminary report". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 11 (6): 283–288.

Greenblatt, E; Butler, J; Venegas, J; Winkler, T (2014). "Pendelluft in the bronchial tree". American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiologyv. 117 (9): 979–988. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00466.2014. PMC 4217048. PMID 25170072.

Morris, L (1952). "A new vaporizer for liquid anesthetic agents". Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 13 (6): 587–593. PMID 12986220.

Morris, L (2006). "Copper kettle revisited". Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 104 (4): 881–884. PMID 16571985.

Tabern, DL; Volwiler, EH (October 1935). "Sulfur-containing barbiturate hypnotics". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 57 (10): 1961–3. doi:10.1021/ja01313a062.

Eisleb, 0. & Schaumann, 0. (1939) Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 65, 967-968.

Scott C. C., Chen K. K. (1946). Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 87: 63–71. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Rowbotham, ES; Magill, I (1921). "Anæsthetics in the Plastic Surgery of the Face and Jaws". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 14 (Sect Anaesth): 17–27. PMC 2152821. PMID 19981941.

Magill, I (14 July 1923). "The provision for expiration in endotracheal insufflations anaesthesia". The Lancet. 202 (5211): 68–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)37756-5.

Magill, I (December 1928). "Endotracheal Anæsthesia". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 22 (2): 85–8. PMC 2101959. PMID 19986772.

Magill, I (November 1930). "Technique in Endotracheal Anaesthesia". British Medical Journal. 2 (1243): 817–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1243.817-a. PMC 2451624. PMID 20775829.

Thomas, KB (July – August 1978). "Sir Ivan Whiteside Magill, KCVO, DSc, MB, BCh, BAO, FRCS, FFARCS (Hon), FFARCSI (Hon), DA. A review of his publications and other references to his life and work". Anaesthesia. 33 (7): 628–34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1978.tb08426.x. PMID 356665.

McLachlan, G (September 2008). "Sir Ivan Magill KCVO, DSc, MB, BCh, BAO, FRCS, FFARCS (Hon), FFARCSI (Hon), DA, (1888–1986)". Ulster Medical Journal. 77 (3): 146–52. PMC 2604469. PMID 18956794.

Magill, I (October 1920). "Appliances and Preparations". British Medical Journal. 2 (3122): 670. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.571.670. PMC 2338485. PMID 20770050.

Magill, I (6 March 1926). "An improved laryngoscope for anaesthetists". The Lancet. 207 (5349): 500. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)17109-6.

Magill, I (30 April 1921). "A Portable Apparatus for Tracheal Insufflation Anaesthesia". The Lancet. 197 (5096): 918. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)55592-5.

Magill, I (11 June 1921). "Warming Ether Vapour for Inhalation". The Lancet. 197 (5102): 1270. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)24908-3.

Magill, I (4 August 1923). "An apparatus for the administration of nitrous oxide, oxygen, and ether". The Lancet. 202 (5214): 228. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)22460-X.

Gravenstein, Joachim (January 1998). "Henry K. Beecher : The Introduction of Anesthesia into the University". Anesthesiology. 88 (1): 245–253. doi:10.1097/00000542-199801000-00033. PMID 9447878.

Betcher, A (1977). "The civilizing of curare: a history of its development and introduction into anesthesiology". Anesthesia \& Analgesia. 56 (2): 305–319. PMID 322548.

Macintosh, RR (13 February 1943). "A new laryngoscope". The Lancet. 241 (6233): 205. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)89390-3.

Scott, J; Baker, PA (July 2009). "How did the Macintosh laryngoscope become so popular?". Paediatric Anaesthesia. 19 (Suppl 1): 24–9. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03026.x. PMID 19572841.

Macintosh, RR (1 January 1949). "Marxist Genetics". British Medical Journal. 1 (4591): 26–28. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4591.26-b. PMC 2049235.

Venn, PH (March 1993). "The gum elastic bougie". Anaesthesia. 48 (3): 274–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb06936.X.

Viswanathan, S; Campbell, C; Wood, DG; Riopelle, JM; Naraghi, M (November – December 1992). "The Eschmann Tracheal Tube Introducer. (Gum elastic bougie)". Anesthesiology Review. 19 (6): 29–34. PMID 10148170.

Henderson, JJ (January 2003). "Development of the 'gum-elastic bougie'". Anaesthesia. 58 (1): 103–4. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.296828.x. PMID 12492697.

Raventos, J; Goodall, R (1956). "The Action of Fluothane-A New Volatile Anaesthetic". British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 11 (4): 394–410. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1956.tb00007.x. PMC 1510559. PMID 13383118.

Stanley, TH; Egan, TD; Van Aken, H (February 2008). "A Tribute to Dr. Paul A. J. Janssen: Entrepreneur Extraordinaire, Innovative Scientist, and Significant Contributor to Anesthesiology". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 106 (2): 451–62. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181605add. PMID 18227300.

Janssen, PA; Niemegeers, CJ; Schellekens, KH; Verbruggen, FJ; Van Nueten, JM (March 1963). "The pharmacology of dehydrobenzperidol, a new potent and short acting neuroleptic agent chemically related to Haloperidol". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 13: 205–11. PMID 13957425.

de Castro J, Mundeleer P (1959). "Anesthésie sans barbituriques: la neuroleptanalgésie". Anesthésie, Analgésie, Réanimation (in French). 16: 1022–56. ISSN 0003-3014.

Nilsson E, Janssen PA (1961). "Neurolept-analgesia: an alternative to general anesthesia". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 5 (2): 73–84. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1961.tb00085.x. ISSN 0001-5172. PMID 13729171.

Aubry, U; Carignan, G; Chare-Tee, D; Keeri-Szanto, M; Lavallee, JP (May 1966). "Neuroleptanalgesia with fentanyl-droperidol: An appreciation based on more than 1000 anaesthetics for major surgery". Canadian Anaesthetists' Society Journal. 13 (3): 263–71. doi:10.1007/BF03003549. PMID 5961929.

Corssen, G; Domino, EF; Sweet, RB (November – December 1964). "Neuroleptanalgesia and Anesthesia". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 43 (6): 748–63. doi:10.1213/00000539-196411000-00028. PMID 14230731.

Reyes JC, Wier GT, Moss NH, Romero JB, Hill R (September 1969). "Neuroleptanalgesia and anesthesia: Experiences in 60 poor risk geriatric patients". South Dakota Journal of Medicine. 22 (9): 31–3. PMID 5259472.

J., PA; Eddy, NB (February 1960). "Compounds Related to Pethidine--IV. New General Chemical Methods of Increading the Analgesic Activity of Pethidine". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2 (1): 31–45. doi:10.1021/jm50008a003. PMID 14406754.

Janssen, PA; Niemegeers, CJ; Dony, JG (1963). "The inhibitory effect of fentanyl and other morphine-like analgesics on the warm water induced tail withdrawal reflex in rats" (PDF). Arzneimittel-Forschung. 13: 502–7. PMID 13957426.

Niemegeers, CJ; Schellekens, KH; Van Bever, WF; Janssen, PA (1976). "Sufentanil, a very potent and extremely safe intravenous morphine-like compound in mice, rats and dogs". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 26 (8): 1551–6. PMID 12772.

Spierdijk J, van Kleef J, Nauta J, Stanley TH, de Lange S (1980). "Alfentanil: a new narcotic induction agent". Anesthesiology. 53: S32. doi:10.1097/00000542-198009001-00032.

Niemegeers CJ, Janssen PA (1981). "Alfentanil (R39209)-a particularly short acting intravenous narcotic analgesic in rats". Drug Development Research. 1: 830–8. doi:10.1002/ddr.430010111. ISSN 0272-4391.

De Vos, V (22 July 1978). "Immobilisation of free-ranging wild animals using a new drug". Veterinary Record. 103 (4): 64–8. doi:10.1136/vr.103.4.64. PMID 685103.

Laduron, P; Janssen, PF (August 1982). "Axoplasmic transport and possible recycling of opiate receptors labelled with 3H-lofentanil". Life Sciences. 31 (5): 457–62. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(82)90331-9. PMID 6182434.

Doenicke A, Kugler J, Penzel G, Laub M, Kalmar L, Kilian I, Bezecny H (August 1973). "[Cerebral function under etomidate, a new non-barbiturate i.v. hypnotic]". Anaesthesist (in German). 22 (8): 353–66. ISSN 0003-2417. PMID 4584133. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

Morgan, M; Lumley, Jean; Whitwam, J.G. (26 April 1975). "Etomidate, a New Water-Soluble Non-barbiturate Intravenous Induction Agent". The Lancet. 305 (7913): 955–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(75)92011-5. PMID 48126.

Murphy, P (July 1967). "A fibre-optic endoscope used for nasal intubation". Anaesthesia. 22 (3): 489–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1967.tb02771.x. PMID 4951601.

Wheeler M and Ovassapian A (2007). "Chapter 18: Fiberoptic endoscopy-aided technique". In Benumof, JL (ed.). Benumof's Airway Management: Principles and Practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby-Elsevier. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-323-02233-0. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Agrò, F; Barzoi, G; Montecchia, F (May 2003). "Tracheal intubation using a Macintosh laryngoscope or a GlideScope in 15 patients with cervical spine immobilization". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 90 (5): 705–6. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg560. PMID 12697606.

Cooper, RM; Pacey, JA; Bishop, MJ; McCluskey, SA (February 2005). "Early clinical experience with a new videolaryngoscope (GlideScope) in 728 patients". Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 52 (2): 191–8. doi:10.1007/BF03027728. PMID 15684262.

Tonner, PH (August 2006). "Xenon: one small step for anaesthesia...? (editorial review)". Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 19 (4): 382–4. doi:10.1097/01.aco.0000236136.85356.13. PMID 16829718. Retrieved 15 September 2010. |